From Modernism to Postmodernism

Click each image to view additional photos

The transformative turn from 19th to 20th century society arose from a convergence of numerous phenomena: the irrevocability of the Industrial Revolution and mass production, urbanization, wars, technology, and a general human drive to improve and reshape our surroundings in the name of progress. Modernism as a movement was born philosophically from this series of transformations, and permeated every corner of the arts.

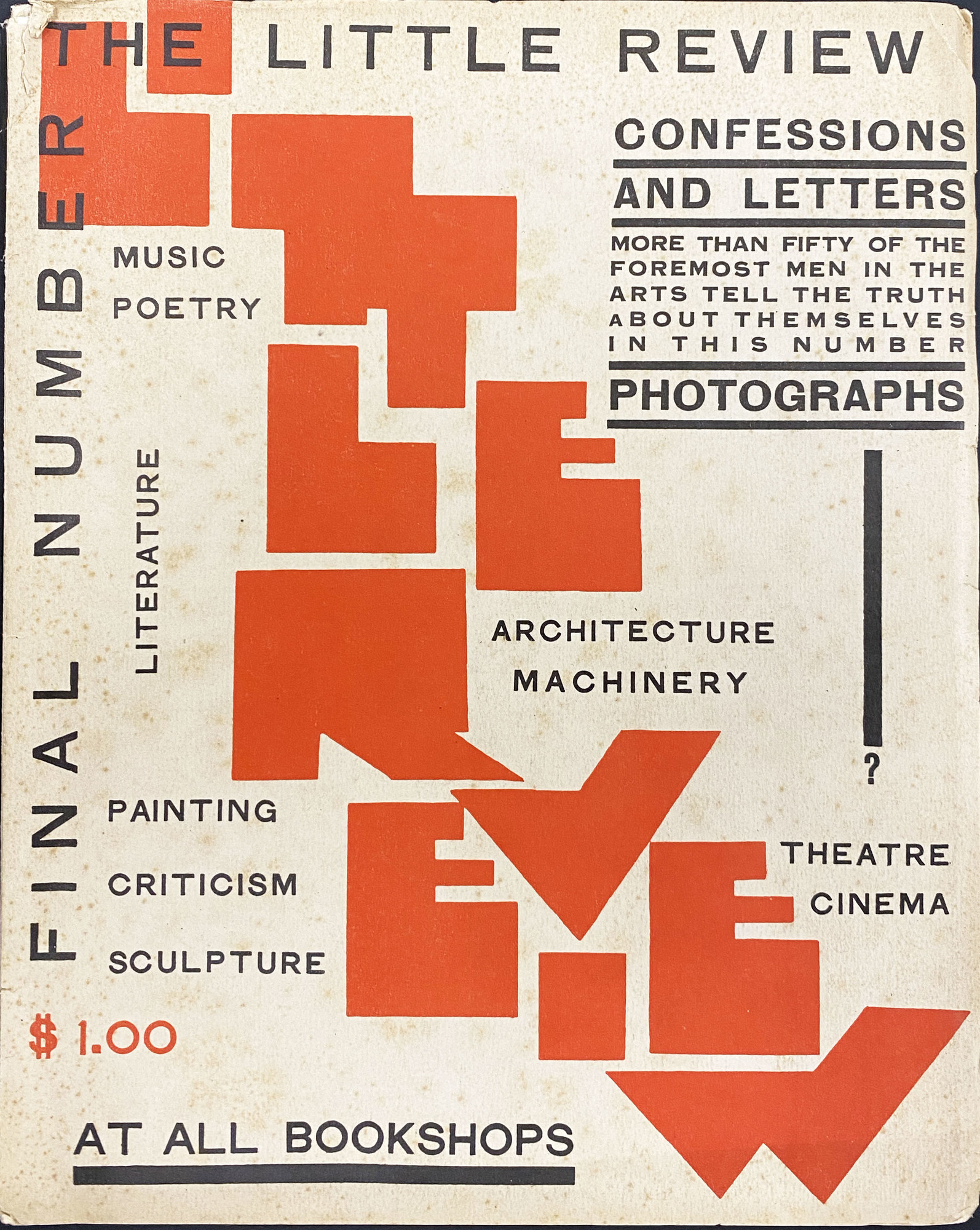

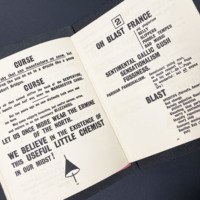

Literary modernism arose through experimental periodicals known as “little magazines,” where many of the authors associated with the movement were first published. Little magazines deserve mention in a design history context because of the illustrations, graphic quality and artistic collaborations found in many of them. Shown here are two design-friendly examples: the Wyndham Lewis-edited Blast, and the Little Review, founded by Margaret Anderson, with help from Jane Heap and Ezra Pound. Little Review became graphically exciting in 1919 and regularly featured surrealist and Dadaist art, and the final issue, shown here, is a hilarious series of “Confessions and Letters” from over 50 individuals who responded to a questionnaire, including artists Max Ernst, Pablo Picasso, László Moholy-Nagy, and Tristan Tzara. Blast is a formidable typographical experience containing the manifesto for the short-lived Vorticist movement, which initially drew influence from but eventually blasted Italian Futurist Filippo Marinetti.

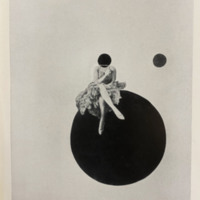

The founding of the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany, in 1919 was a pivotal moment in design history. The Bauhaus school took cues from art nouveau and the Arts & Crafts movement that merged aesthetic with function, to achieve the idea of gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) across a range of applied arts, including furniture construction, printing, ceramics, industrial design, architecture. Its approach, however, was decidedly modernist, and also derived influence from the Russian avant-garde movements. Founded by Walter Gropius, and with prominent faculty including Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and László Moholy-Nagy, the Bauhaus had a profound and irrevocable influence on all aspects of art and design that would follow. Moholy-Nagy’s tirelessly experimental work in photography, photomontage and photogram, collected in his first monograph 60 Fotos, secured their place in modernism and design history. Typography, likewise, shifted towards a modern, universal method of communication. This new, more visual experience of typography was codified in Jan Tschichold’s “Elementare Typographie,” a special issue of the trade journal Typographische Mitteilungen in 1925, and more thoroughly in his 1928 book, Die Neue Typographie.

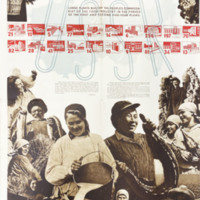

In the Soviet Union, the avant-garde movements that anticipated modernism, including Suprematism, Constructivism, and Futurism, peaked around the Bolshevik Revolution. Under Stalin, these movements were snuffed out by state-sponsored Socialist Realism, which rejected art for art’s sake and upheld images and icons of proletarian daily life and the party’s ideology. However, many avant-gardist design icons, including Aleksander Rodchenko and El Lissitzky, were brought on to contribute to party publications like the incredible folio-sized magazine, USSR In Construction. Running mainly from 1930-1941, each issue was dedicated to lauding the innovations and advancements of the Soviet Union in a particular industry, with gorgeous photomontage style throughout.

Jumping forward not with the intention of omitting nearly five decades of incredible design, but to illustrate a shift made possible in part by digital technology, 20th century modernism takes its leave here. Starting in the late 1970s and on full, grotesque display by the mid-1980s, postmodern design flourished during the “designer decade.” A revolt against the cold, minimal logic of modernism that permeated the greater part of 20th century design, postmodernism invited playfulness, ugliness, irony and excess. Authority was to be disobeyed, reality was no longer objective and neon reigned supreme! The New Wave designers, influenced by punk rock and postmodern theory and trained in the Swiss Style, broke from order and grid-adherence to stretch the limits of comprehension and readability. April Greiman was the first among them to embrace computer graphics in her work, enabling a new complexity that changed the field entirely. Her special 1986 issue of Design Quarterly magazine unfolds to a 3’ x 6’ poster of her digitized naked body layered amid image and text, asks the reader “Does it make sense?” referring, of course, not only to the work in question, but the medium as a whole. Her response: “It makes sense if you give it sense.”